The Women Who Remade Kurdish Resistance

Opinions 01:42 PM - 2026-02-09 PUKMEDIA

PUKMEDIA

Manish Rai, Geopolitical Analyst and Columnist for Middle-East.

Written by Manish Rai, Geopolitical Analyst and Columnist for Middle-East.

Kurdish women fighters have transformed armed resistance into a broader political project.

Any serious attempt to understand the Middle East’s rapidly shifting geopolitical terrain must begin with the Kurds. Yet even within that already marginalised story, one force has too often been treated as a footnote rather than a driver of change: Kurdish women. For decades, they have confronted a double bind—gender discrimination layered atop ethnic repression—and still managed to reshape the political and military landscape of the region. Nowhere is this more visible than among Kurdish women fighters, whose role in conflict and governance has challenged entrenched norms across the Middle East.

At the center of this transformation stands the Women’s Protection Units, the YPJ, an all-female fighting force formed in 2013 in northern Syria. The YPJ rose to global prominence during the fight against ISIS, defending Kurdish-held territory in Syria while earning a reputation for discipline and battlefield effectiveness. In some cases, women commanders in the YPJ have led male fighters—an inversion of traditional hierarchies that has unsettled both enemies and allies. Yet the YPJ’s mission has never been purely military. Alongside territorial defense, the group explicitly frames its struggle as one for women’s emancipation and the dismantling of patriarchal systems that have long defined political life in the region.

That ideological commitment took root amid the chaos of Syria’s civil war, particularly in Rojava, where Kurdish women achieved a degree of political, economic, and social equality that many states still struggle to realize. Grounded in the slogan “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi,” or “Woman, Life, Freedom,” the Rojava model emphasizes grassroots democracy, communal governance, and ecological balance, while openly confronting patriarchy. The YPJ did not emerge in isolation. Its fighters are heirs to a long lineage of Kurdish women revolutionaries who resisted authoritarianism and dictatorship long before the Syrian conflict erupted.

Among them was Leyla Qasim, a university student who challenged Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime in the early 1970s. After a televised show trial, she was executed by hanging, becoming a symbol of Kurdish resistance. Decades later, Hevrin Khalaf, a prominent Kurdish politician devoted to fostering cooperation between Muslims and Christians in Syria, was abducted and executed by Salafi extremists in 2019. These women are remembered not merely as victims, but as architects of a political tradition that refuses submission.

The precedent extends beyond Syria. In neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan, women contributed to the Peshmerga forces in ways that were both innovative and deeply consequential during the Kurdish-Iraqi War. One of the most striking figures was Margaret George, an Assyrian Kurd who commanded a small Peshmerga battalion near Akra. Formerly a hospital worker, George joined the armed struggle after Jash forces attacked her village. After her death, she was memorialised as the “Joan of Arc of the Peshmerga,” a folk hero whose image was carried by thousands of fighters. Described by comrades as brilliant and fearless, she remains a powerful symbol of women’s participation in Kurdish resistance.

Women have technically been permitted to serve in the Peshmerga since the 1970s, but their formal integration began in 1996, when the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan established the first all-female unit. Since then, hundreds of women have joined the ranks, with some ascending to senior positions. This evolution reflects a deeper historical pattern. Kurdish women have long held positions of authority in military, political, and religious life. Figures such as Kara Fatima Khanum and Khanzade Sultan illustrate this legacy. After her husband’s death in the mid-19th century, Kara Fatima Khanum assumed leadership of a major tribe in eastern Anatolia and later led 300 fighters in the Crimean War on behalf of the Ottomans. Centuries earlier, Khanzade Sultan governed the Harrir and Soran regions east of Erbil during the reign of Sultan Murad IV, commanding tens of thousands of troops and launching military campaigns against Iran.

In both Iraqi Kurdistan and Rojava, modern Kurdish military organizations have expanded pathways for women’s participation, contributing to measurable improvements in women’s rights. Within areas controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government, women’s social and political standing has steadily improved. Their assertiveness in combat reflects a broader reality: the Kurdish national movement and the Kurdish women’s movement developed in tandem. The struggle for national recognition and the fight for gender equality have been inseparable.

To better understand this dynamic, I interviewed Major General Osman Resha, spokesperson for the Ministry of Peshmerga Affairs. He emphasised that women in the Peshmerga serve across a wide range of roles, including leadership positions. More significantly, he noted that women’s participation has become institutionalised, with increasing numbers enrolling in military academies for both scientific and combat training. The implication is clear: women’s roles within the Peshmerga are not symbolic or temporary, but structural and expanding.

That transformation reached its apex with the rise of ISIS in 2014. In Rojava, YPJ fighters stood on the front lines, while in southern Kurdistan, female Peshmerga played a decisive role, often at great personal cost. These women defended villages, rebuilt communities, and helped establish councils and schools amid devastation. Their fight, however, cannot be reduced to a campaign against jihadist violence alone. Kurdish women fighters see themselves as defending dignity itself—particularly women’s dignity—in a region where both are routinely denied.

More news

-

U.S. Issues Fresh Guidance to Vessels Transiting Strait of Hormuz

10:24 PM - 2026-02-09 -

Iraqi Justice Minister Discusses Prisoner Transfer Agreement with Georgian Ambassador

07:26 PM - 2026-02-09 -

Iraq's National Security Service Executes Convicted Murderer of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr

01:57 PM - 2026-02-09 -

University of Kobani Condemns Deadly Attack, Appeals for Probe After Student Lost Legs in the Attack

01:18 PM - 2026-02-09

see more

Iraq 07:12 PM - 2026-02-09 PUK Parliamentary Bloc Intensifies Efforts to Ensure Farmers Receive Their Financial Dues

Qubad Talabani Outlines Plan to Restore Sulaymaniyah Sports Club’s Leading Status

05:16 PM - 2026-02-09

EU Allocates €8 Million to Support Community Reintegration in Iraq

04:09 PM - 2026-02-09

Iraqi Parliament Moves to Amend Rules Governing Parliamentary Committees

02:21 PM - 2026-02-09

Most read

-

Iraq's National Security Service Executes Convicted Murderer of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr

Iraq 01:57 PM - 2026-02-09 -

Qubad Talabani Outlines Plan to Restore Sulaymaniyah Sports Club’s Leading Status

Kurdistan 05:16 PM - 2026-02-09 -

The Women Who Remade Kurdish Resistance

Opinions 01:42 PM - 2026-02-09 -

EU Allocates €8 Million to Support Community Reintegration in Iraq

Iraq 04:09 PM - 2026-02-09 -

Remembering President Mam Jalal’s Historical Pleading

Kurdistan 09:19 AM - 2026-02-09 -

PUK Politburo: President Mam Jalal’s Historic Pleading Became the Cornerstone of Article 140

P.U.K 11:21 AM - 2026-02-09 -

PUK VP: Mam Jalal’s Political Legacy Remains Rich With Advocacy for Kurdistan

P.U.K 10:09 AM - 2026-02-09 -

University of Kobani Condemns Deadly Attack, Appeals for Probe After Student Lost Legs in the Attack

World 01:18 PM - 2026-02-09

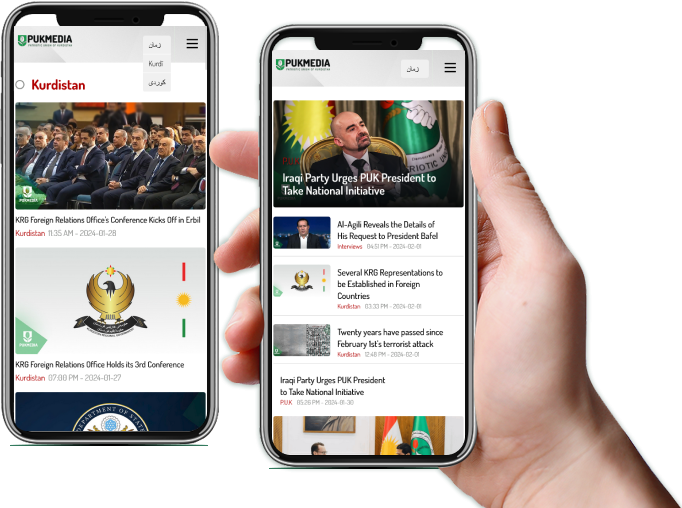

Application

Application